Looking for an edge with the classic Quicksort algorithm

Smart Sort

© Lead Image © Olga Yastremska, 123RF.com

If you wanted to assign a flavor to the Quicksort algorithm, it would be sweet and sour. Sweet, because it is very elegant; sour, because typical implementations sometimes leave more questions than they answer.

The Quicksort sorting algorithm has been around for 60 years, and, if implemented properly, it is still the fastest option for many sorting tasks. According to the description on Wikipedia, a well designed Quicksort is "…somewhat faster than Merge sort and about two or three times faster than Heapsort."

Many Linux users today have studied Quicksort at some point in the past, through a computer science class or other training scenario, but unless you are working as a professional programmer, chances are it has been a few years since you have taken the time to ponder the elegant Quicksort algorithm. Still, sorting goes on all the time on Linux networks. You don't have to be a full-time app developer to conjure up an occasional script to rank results or order a set of values extracted from a log file. This article explores some of the nuances of the classic Quicksort.

Quicksort ABC

The Quicksort [1] algorithm originated with Tony Hoare [2], who first developed it in 1959 and published it in 1961. Quicksort is what is known as a divide-and-conquer algorithm. One element in the array is chosen to be the pivot element. All elements smaller than the pivot element are then grouped in a sub-array before it, and all elements larger than the pivot element are placed in a sub-array after it. This process is then repeated with the sub-arrays: a pivot element is chosen, with smaller elements placed in a sub-array before and larger elements placed in a sub-array after. After a finite number of steps, the size of the sub-arrays becomes one, and at that point, the whole array has been sorted.

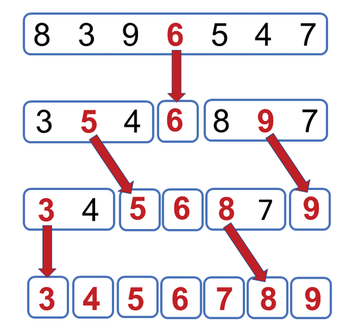

Too complicated? Figure 1 sums up the Quicksort algorithm. Boxes containing only one red number are already in the right position. In the first row, the number 6 is the pivot element. Now all of the elements are sorted in relation to 6. In the second row, the 5 and the 9 act as the new pivot elements. Now the partial arrays are sorted relative to 5 and 9. The result is the third row, where almost all of the elements are already sorted. Only the 8 (the new pivot element) has to swap places with the 7. If you would prefer an animated clip of the Quicksort algorithm, check out the Quicksort page on Wikipedia [1].

If the array contains n elements, an average of n*log(n) sorting steps are needed. The log(n) factor results from the fact that the algorithm halves the array in each step. In a worst-case scenario, Quicksort requires n*n sorting steps. To illustrate this worst-case scenario, consider that, in Figure 1, the middle element served as the pivot element. But any other element could also serve as the pivot element. If the first element is the pivot element and the array is already sorted in ascending order, the array must be halved exactly n times, which would be the (very unlikely) worst case. Note that a few lines of text are all I needed to describe the elegant and highly efficient Quicksort algorithm, along with its performance characteristics.

First Encounter

The classic Quicksort implementation in C lacks charm and is quite successful at disguising its elegant design, as Listing 1 demonstrates. I won't provide a full description of the code; however, one observation is very interesting.

Listing 1

Quicksort in C

01 void quickSort(int arr[], int left, int right) {

02 int i = left, j = right;

03 int tmp;

04 int pivot = arr[abs((left + right) / 2)];

05 while (i <= j) {

06 while (arr[i] < pivot) i++;

07 while (arr[j] > pivot) j--;

08 if (i <= j) {

09 tmp = arr[i];

10 arr[i] = arr[j];

11 arr[j] = tmp;

12 i++; j--;

13 }

14 }

15 if (left < j) quickSort(arr, left, j);

16 if (i < right) quickSort(arr, i, right);

17 }

In Lines 9 to 11, the code overwrites the existing elements. Thus, the algorithm runs in-place and assumes mutable data. A nice expression has been established for the task of overwriting old values with new ones in functional programming: destructive assignment [3]. This takes us neatly to the next topic: in functional programming languages like Haskell, Quicksort is represented in a far more elegant way.

Second Encounter

In Haskell, data is immutable, which precludes destructive assignment by design. The Haskell-based Quicksort algorithm in Listing 2 creates a new list in each iteration, rather than acting directly on the array as in Listing 1. Quicksort in two lines? Is that all there is to it? Yes.

Listing 2

Quicksort in Haskell

qsort [] = [] qsort (x:xs) = qsort [y | y <- xs, y < x] ++ [x] ++ qsort [y | y <- xs, y >= x]

The qsort algorithm consists of two function definitions. The first line applies the defined Quicksort to the empty list. The second line represents the general case, where the list consists of at least one element: x:xs. Here, by convention, x denotes the beginning of the list and xs denotes the remainder.

The strategy of the Quicksort algorithm can be implemented almost directly in Haskell:

- use the first element of the list

xas the pivot element; - insert (

(++)) all elements inxsthat are lesser thanx((qsort [y | y <- xs, y < x])) in front of the one-element list[x]; - append all elements in

xsthat are at least as large asxto the list[x]((qsort [y | y <- xs, y >= x])).

The recursion ends when Quicksort is applied to the empty list. Admittedly, the compactness of Haskell seems unusual. However, this Quicksort algorithm can be implemented in any programming language that supports list comprehension – which leads to the more mainstream Python programming language in Listing 3.

Listing 3

Quicksort in Python

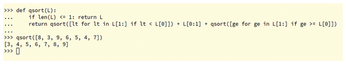

def qsort(L): if len(L) <= 1: return L return qsort([lt for lt in L[1:] if lt < L[0]]) + L[0:1] + qsort([ge for ge in L[1:] if ge >= L[0]])

The description of the Haskell algorithm can be applied almost verbatim to Python. The subtle difference is that in Python, L[0:1] acts as the first element and you express the list concatenation in Python with the + symbol. The algorithm reliably performs its services in Figure 2.

Buy this article as PDF

(incl. VAT)

Buy Linux Magazine

Subscribe to our Linux Newsletters

Find Linux and Open Source Jobs

Subscribe to our ADMIN Newsletters

Support Our Work

Linux Magazine content is made possible with support from readers like you. Please consider contributing when you’ve found an article to be beneficial.

News

-

TUXEDO Computers Unveils Linux Laptop Featuring AMD Ryzen CPU

This latest release is the first laptop to include the new CPU from Ryzen and Linux preinstalled.

-

XZ Gets the All-Clear

The back door xz vulnerability has been officially reverted for Fedora 40 and versions 38 and 39 were never affected.

-

Canonical Collaborates with Qualcomm on New Venture

This new joint effort is geared toward bringing Ubuntu and Ubuntu Core to Qualcomm-powered devices.

-

Kodi 21.0 Open-Source Entertainment Hub Released

After a year of development, the award-winning Kodi cross-platform, media center software is now available with many new additions and improvements.

-

Linux Usage Increases in Two Key Areas

If market share is your thing, you'll be happy to know that Linux is on the rise in two areas that, if they keep climbing, could have serious meaning for Linux's future.

-

Vulnerability Discovered in xz Libraries

An urgent alert for Fedora 40 has been posted and users should pay attention.

-

Canonical Bumps LTS Support to 12 years

If you're worried that your Ubuntu LTS release won't be supported long enough to last, Canonical has a surprise for you in the form of 12 years of security coverage.

-

Fedora 40 Beta Released Soon

With the official release of Fedora 40 coming in April, it's almost time to download the beta and see what's new.

-

New Pentesting Distribution to Compete with Kali Linux

SnoopGod is now available for your testing needs

-

Juno Computers Launches Another Linux Laptop

If you're looking for a powerhouse laptop that runs Ubuntu, the Juno Computers Neptune 17 v6 should be on your radar.