Fixing broken packages in Debian systems

Package Repair

© stylephotographs, 123RF.com

When human error stumps the Debian package manager, familiar tools like apt-get, aptitude, and dpkg can help restore functionality.

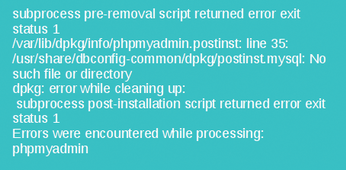

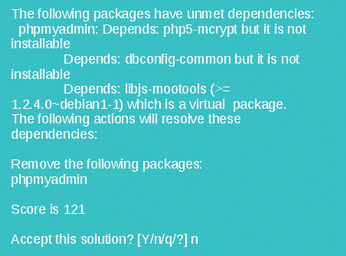

The Debian package manager pioneered automatic dependency resolution during software installation. However, like any software, it cannot protect against human error. Maybe you installed the wrong package from Testing or Unstable repositories or gambled on Experimental. Maybe you installed a flawed third-party package or mixed packages from different Debian derivatives. Or maybe the maintainer made a mistake or a major technology change has happened, and you are not to blame at all. But in all of these cases, you either receive an error message (Figure 1) or a ranked list of possible solutions (Figure 2), and suddenly you are unable to install, remove, or update anything until the problem completes its efforts and returns you to a waiting command prompt.

If you are patient, a new version of the problem package will be released that fixes the problem. The only trouble is, the new version might not be released for weeks, depending on where Debian, or your Debian derivative, like Linux Mint or Ubuntu, happens to be in its development cycle. Even after filing a bug, it can sometimes take time to resolve the problem. Probably, then, you want to take more active steps.

Fortunately, the tools you need are ones you are likely already be familiar with: apt-get [1], the package manager's front end; aptitude [2], the popular command-line interface; and dpkg [3], the basic package tool. All three have the structure

COMMAND SUBCOMMAND PACKAGES

as well as many of the same features for installing and removing packages.

Apt-get and dpkg are installed by default on any Debian or Debian derivative system. However, if you have risky habits, like constantly taking the latest package versions from Unstable, you should make sure that aptitude is installed, as well as other useful tools such as script, which can log your recovery efforts, or equivs, which builds packages that contain only dependency information. You should also bookmark the Debian bug tracker [4], so you can begin your troubleshooting by seeing whether others have faced the problem on which you are working.

In all these tools, you should gather whatever information you can about the state of the packages involved. However, actually fixing the problem is likely to take you far beyond the usual internal commands like install and remove.

Making Repairs with apt-get

When apt-get announces that you have broken dependencies and suggests solutions, very occasionally, removing problem packages with

apt-get remove PACKAGES

can solve the problem. On the principle of starting with the simplest solution, try this command, but don't be surprised if it does not succeed.

Another relative long shot is editing package sources to get newer versions of the problem package(s), using apt-get update to make them available. In particular, search for a mirror site with more recent packages than your usual ones to add to the file /etc/apt/sources.list.

A more promising approach is running

apt-get dist-upgrade --no-upgrade

to upgrade all the packages installed on the system. Do not use apt-get upgrade, since the last thing you want to do is complicate the problem by adding more packages to the mix.

Another possibility is to force completion of an install with:

apt-get dist-upgrade -f

Sometimes, specifying some or all of the packages mentioned in apt-get messages will work instead:

apt-get install -f PACKAGES

Alternatively, try

apt-get remove -f packages

but read the summary of what will happen carefully before continuing the command. For some obscure reason, all these commands may work the second, third, or even the fourth time you run them, so run them several times before giving up on them. You can also try specifying the repository and full package name by adding the -t option to any of these commands.

However, if you try all these solutions and have no luck, you have exhausted the capabilities of apt-get and need to try another command.

Aptitude Dancing

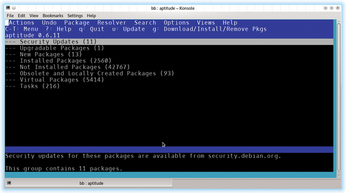

When run without options, aptitude opens an ncurses interface to the Debian package manager (Figure 3). However, what many users do not know is that aptitude contains many of the same tools as apt-get and dpkg for fixing broken packages, as well as several extra of its own.

For example, you may be able to resolve problems by using the markauto command to mark packages as being automatically installed, or unmarkauto to mark them as manual installations. Another useful command is -t RELEASE, which specifies which release version to use, or its counterpart forbid-version to specify a version not to use.

Another useful pair of tools is why and why-not. Both are followed by a dependency. The why command shows why a dependency would be required, whereas why-not shows why a dependency produces a conflict. The results of both can indicate how a subset of broken packages involving conflicts with another package can be resolved.

However, the most popular feature of aptitude is the Resolver menu. The menu lists the package manager's suggested solutions to dependency problems and allows you to approve and reject them. Often, this menu alone solves problems that apt-get, dpkg, or other features of aptitude cannot, although at the cost of hiding exactly what it is doing.

Escalating to dpkg

Because dpkg is a lower-level package than apt-get, it includes many features that apt-get and aptitude do not. As its man page shows, dpkg is especially useful for reading detailed information about packages, including the state it is in, and for filtering the information displayed. You might be able to run dpkg with the option --forget-old-unavailable, or --clear-selections to remove problems, or --audit (-C) to receive advice on what actions to try. However, more often, dpkg options or commands, such as dpkg-query, will be most useful in filtering or gathering background information that can help you develop a solution. The --yet-to-unpack option can be especially useful when you have been looking for solutions for some time and don't care to scroll back in your history for the names of the problem packages.

An especially powerful dpkg option is --purge (-P). --purge is a more powerful version of remove, deleting not only the package, but all records of it, including the configuration files. In addition to removing the package, --purge also runs its postrm (post-removal script). While you are troubleshooting, this thorough deletion can simplify the problem's background and sometimes even solve the problem itself. The dpkg man page will give you more information.

Another important option is:

dpkg install --ignore-depends=PACKAGE

This option is misnamed, since it does check for dependencies but only reports conflicts between packages. Often, it can be the solution for which you are looking.

An equally powerful solution is:

dpkg --configure -a

which configures all partially installed packages. In my experience, this command fixes more broken dependencies than any other option mentioned in this article, although it is not infallible.

If not, then take a detailed look at --force-things THING, as well as --no-force-things and --refuse-things. Just as --purge is an enhanced version of remove, so --force-things is a fine-tuned version of the apt-get --force option. Probably, you probably want to avoid completions of these commands such as bad-version, remove, or overwrite unless you are absolutely confident of what you are doing. However other completions, such as downgrade, configure-any, and remove-reinstreq may provide solutions. But --force-things can bring your system down when used carelessly, so consult --force-help, as well as the man pages, before using it.

In fact, dpkg as a whole can be so deadly that you should use --no-act [--dry-run, --simulate] to do a dry run of any action, simply on the off-chance of unexpected effects. The simulation will not tell you in so many words that your system or desktop environment will crash, but studying the list of affected files should warn you that you risk making your situation worse.

Buy this article as PDF

(incl. VAT)