Implementing fast queries for local files in Go

Programming Snapshot – Go

To find files quickly in the deeply nested subdirectories of his home directory, Mike whips up a Go program to index file metadata in an SQLite database.

Those were the days when you could simply enter a line of code or a variable name into Google's code search page (Figure 1), and the data crawler would reveal in next to no time the open source repositories in which it appeared. Unfortunately, Google discontinued the service several years ago, probably because it failed to generate sufficient profit.

But not all is lost, because the GitHub Codesearch [1] project, with its indexer built in Go, at least lets you browse locally available repositories, index them, and then search for code snippets in a flash. Its author, Russ Cox, then an intern at Google, explained later how the search works [2].

How about using a similar method to create an index of files below a start directory to perform quick queries such as: "Which files have recently been modified?" "Which are the biggest wasters of space?" Or "Which file names match the following pattern?"

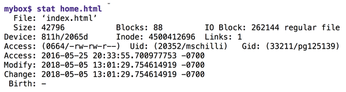

Unix filesystems store metadata in inodes, which reside in flattened structures on disk that cause database-style queries to run at a snail's pace. To take a look at a file's metadata, run the stat command on it and take a look at the file size and timestamps, such as the time of the last modification (Figure 2).

Newer filesystems like ZFS or Btrfs take a more database-like approach in the way they organize the files they contain but do not go far enough to be able to support meaningful queries from userspace.

Fast Forward Instead of Pause

For example, if you want to find all files over 100MB on the disk, you can do this with a find call like:

find / -type f -size +100M

If you are running the search on a traditional hard disk, take a coffee break. Even on a fast SSD, you need to prepare yourself for long search times in the minute range. The reason for this is that the data is scattered in a query-unfriendly way across the sectors of the disk.

To speed this up, I want an indexer to collect the metadata at regular intervals (e.g., during quiet periods in the early morning hours) and store them in an SQLite database that I can run a query tool against. The updatedb utility on Linux does similar things so that the user can search for file names at lightning speed with locate.

Because the "Programming Snapshot" series never shies away from new challenges, and this particular edition was being written during a vacation in Hawaii with me in a good mood and plenty of time on my hands, I used the Go programming language for the implementation – just as in the Codesearch project. An SQLite database is used as the index; it stores all data in a single file but packs enough punch to support optimized and reasonably fast queries, even for medium-sized data volumes.

To do this, Listing 1 [3] creates an SQLite database named files.db that inserts a table entry with the fields path (full file path), size (file size), and modified (timestamp of the file's last modification) for each file found in the directory tree.

Listing 1

create.go

01 package main

02

03 import (

04 "database/sql"

05 _ "github.com/mattn/go-sqlite3"

06 )

07

08 func main() {

09 db, err := sql.Open("sqlite3", "./files.db")

10 if err != nil {

11 panic(err)

12 }

13

14 _, err = db.Exec("CREATE TABLE files " +

15 "(path text, modified int, size int)")

16 if err != nil {

17 panic(err)

18 }

19 }

To install the required SQLite driver, the go get tool included in every Go installation retrieves the driver's source code from GitHub, resolves any dependencies, and compiles and installs the result locally:

go get github.com/mattn/go-sqlite3

Scripts like Listing 1 can then load the driver in their import sections under the full name starting with github.com. I had to employ one minor quirk to prevent the rather adamant Go compiler from exploding, though: It apparently felt that loading the driver package imported code that does not appear to be referenced anywhere in Listing 1. Go does not tolerate unnecessary dependencies, but in this case, the driver is actually required, and it is indeed used under the covers in the database/sql libraries. To calm down the Go compiler, line 5 imports the driver under the name _ (underscore), which turns off the is-it-being-used check.

The start of each Go program is a package main with a function main(), as in line 8 of Listing 1. The Open() method there uses the database/sql package, Go's standard database interface (and the SQLite driver under the hood), to open a connection to the files.db flat file database later.

If the file already exists or another error occurs, the return value err contains a value not equal to nil, and line 11 sounds the alarm with panic() and abruptly terminates the program flow.

Old School Error Checking

The SQL command CREATE in line 14 creates a new database table. Here, too, line 16 checks whether an error was returned and terminates with a message if necessary. Go still believes in old-school-style checking of individual return values instead of allowing the programmer to throw exceptions that bubble up for processing at a higher level.

Also, take a closer look at the different assignments in lines 9 and 14, which first use := and then =. The first is Go's assignment with a declaration. If a variable has not yet been declared, the short form declaration with := does the trick.

Watch Out!

If the declaration list of variables with a := assignment contains only variables that have already been declared, though, Go stubbornly refuses to compile the code at all. In this case, the assignment must be made with an =, as in line 14.

Similarly unique to Go are functions with several return values. Often an error variable is contained in the list of values. If it is set to nil, everything is fine. If a return value is of no interest, such as the first return value of db.Exec() in line 14, Go developers type an underscore in place of an unnecessary variable. Picking up only one return value from a function that returns two would result in a compiler error.

The code is easily compiled by entering:

go build create.go

A fraction of a second later a create executable is available; it already contains all the dependencies and libraries, so it can be easily copied to another machine using the same operating system without a pile of dependencies having to be resolved. The resulting binary is about 4.5MB, which is not exactly lightweight either.

Buy this article as PDF

(incl. VAT)