Subverting LibreOffice Impress for Better Slide Shows

Resisting the Lure of Bullet Point Presentations

ByEvery hour of the work day, hundreds of presenters begin a slide show – and, as the presenters begin to drone, thousands of listeners lean back and do their best to stay awake and not look bored. Just as many users of word processors fail to learn how to use them properly, very few presenters ever learn a way to create a slide that holds an audience’s interest or conveys information successfully.

Why are slide shows so hard to pull off? According to information expert Edward Tufte, the problem is that slide shows allow only for an exchange of information from the presenter to the audience. Two-way conversations are so difficult that in The Cognitive Style of PowerPoint, Tufte compares slide shows to a Soviet MayDay rally.

To make matters worse, most presenters reduce their entire talk to a series of slides, each with six or seven bullet points. This effort at summary – by far the most popular format for slide shows – is poorly suited for all but the simplest of ideas (Figure 1). Multiple causality, feedback, or any other complicated connection between ideas, including emotional reactions, is almost impossible to present. This is the point made by Peter Norvig in The Gettysburg PowerPoint address, which reduces Lincoln’s famous speech to a series of bulleted banalities.

Faced with these difficulties, Genevieve Liang and others suggest that slide shows should be avoided altogether. However, this suggestion is going too far. Taking extra effort in planning, outlining, and presenting a slide show can overcoming the medium’s one-way tendencies and make it a useful aid that reinforces your talk instead of overwhelming it.

Deciding to Use a Slide Show

The first step is to decide whether your topic or the purpose of your talk is suitable for a slide show. For example, if you want a presentation to run continuously without a speaker for a booth at a trade fair or you are giving an introductory university lecture, whose purpose is to give a lot of information with next to no audience participation, then a slide show comprising a summary of your thoughts makes sense. It might not be the most effective way to communicate, but it would fit the constraints you are working under.

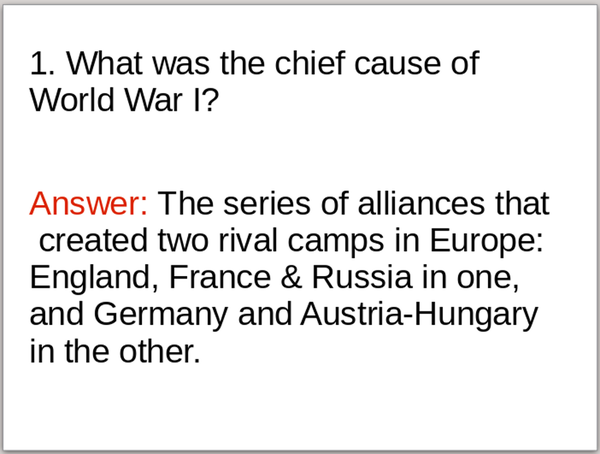

Alternatively, while you may not want a summary slide show, it may be a modern replacement for an overhead projector, showing diagrams and illustrations. Possibly, too, you want to give technical terms so that listeners know how to spell them. You might also use the feature in LibreOffice Impress of revealing one bullet point at a time for quizzes or vocabulary tests (Figure 2). All these uses are justified, because accomplishing the same task without a tool like Impress would be much more difficult, especially if you don’t have a white board or are addressing an audience that is large enough that some listeners might not be able to see what you write or decipher your handwriting.

By contrast, other purposes or circumstances should make you think twice about using a slide show. If you hope for audience participation or if members of the audience will require individual attention, then a slide show, particularly a summary, will work against it. Similarly, if the connections between ideas is essential or the topic involves an understanding of abstract ideas or the connections between between ideas, then a slide show might not be the best medium.

For that matter, if you are present to give a talk, a slide show may be redundant. More seriously, it is a redundancy that competes with you for – and usually wins – the audience’s attention. Often, if you present a summary slide show, you might as well send the summary and not show up at all, a move that will probably add to the audience’s experience.

Make up a list of pros and cons, and make your decision. If you decide not to use a slide show, you can usually win a round of applause simply by announcing your decision as you begin to speak.

Slides Without Summaries

When you prepare a slide, the worst thing you can do is add content and plan the structure at the same time, because adding content is essentially creative, whereas planning structure is essentially analytical. Combining two such different tasks is almost a guarantee that you will do both poorly.

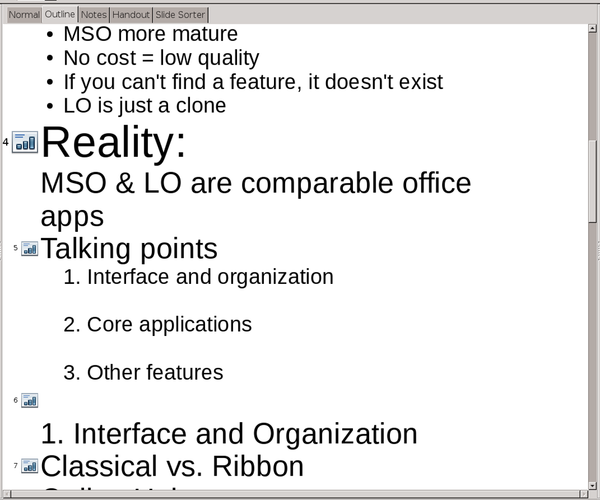

More to the point, doing both at the same time is also likely to leave you with a summary presentation. Instead, do whatever form of outlining works for you, whether it is mind mapping, the Outline view in Impress (Figure 3), or a series of scribbled notes on scrap paper. You might transfer the results to the slide shows’ notes so you can refer to the outline as you speak.

However, don’t stop there. When the outline is complete, go back and indicate in each section the visual aids you are likely to need. Is there a piece of jargon you want to introduce? A place where a diagram is necessary for understanding? A point that you want to introduce with a dramatic question? A moment when you want to ask the audience questions? These are the places where you will need a slide. Exactly how many slides you want will depend on the complexity of the issue and your judgment of the audience’s existing knowledge, but, as a general rule, you will probably need about one slide for every three or four points in the presentation. Anything more, and you may be at risk of summarizing too much.

Summaries should appear in two places at the most: at the beginning of the presentation, where a high-level summary will help orient the audience, and at the end, where a summary helps to emphasize the main points.

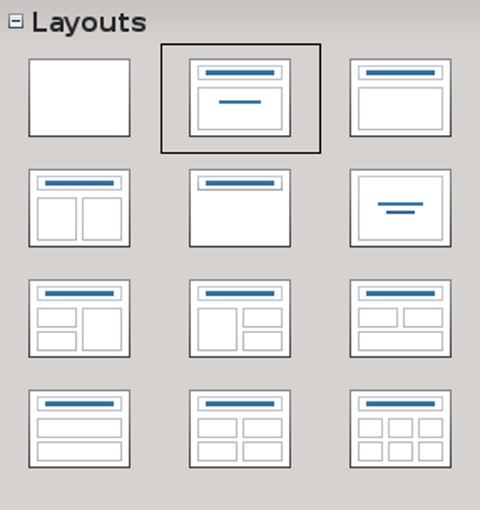

To further reduce the opportunity for summary, do not stick with the default page layouts, which offer bullets by default. Instead, right-click each new slide and select Page Layout. From the side pane, you can then select other designs – particularly the first blank layout or a blank layout that includes a title (Figure 4).

Unfortunately, you cannot edit the Impress Outline styles so that they do not use a bullet list, although you can change the default to a numbered list; however, you can delete the bullet by placing the cursor at the start of a list item’s text and backspacing. Alternatively, press F2 to create a text box rather than using the default bullets, a choice that also gives you greater flexibility in positioning text. With these tactics, you should manage to avoid summarizing instead of talking.

Avoiding Summarizing While Presenting

Even when you minimize summary in the design of your slide show, it can still creep in during presentation.

For one thing, if you are nervous, you might be tempted to summarize because it feels safe and reliable. Even if your slide show avoids summary, your notes do not, and if you are not careful, you may start simply reading them.

However, you can minimize the temptation to summarize by controlling as much of the situation as possible. Practice your talk beforehand, if possible timing each section so that you always know how you are using your time. Carry a backup of your presentation and notes so that, if the slide projector fails, you can still talk. Arrive and set up early to minimize your nervousness.

Most of all, do all you can to avoid looking at the screen yourself, so you can connect with the audience. You can encourage the audience to watch you rather than the slide show by positioning yourself to the left of the screen, where listeners’ eyes are more likely to fall on you as they start to read a screen. Move about as you talk, marking a change of topic with a change of position, distracting the audience from the screen.

Similarly, to prevent just reading from the screen, be well-rehearsed enough that all you need to do is check that each change of slides brings you to where you want to be. Do not read notes, except in an emergency. If possible, have someone else change slides. Do anything you can to unglue your own eyes from the slide show, freeing yourself to watch the audience’s reaction and make eye contact with audience members.

Going Against the Current

Designing and delivering an effective slide show means working against the default design of Impress or any slide show application (Figure 5). A summary slide show might go against all the advice of information designers like Tufte, but, for both users and designers, it is the model of what they expect a presentation to be.

However, you do not have to follow the structural default or audience expectations when giving a slide show, any more than you have to format a text document manually. With some rethinking and a few workarounds, you can deliver a presentation that not only avoids boring your listeners, but leaves them asking questions and maybe – who knows? – teaching them something in the process.

Subscribe to our Linux Newsletters

Find Linux and Open Source Jobs

Subscribe to our ADMIN Newsletters

Support Our Work

Linux Magazine content is made possible with support from readers like you. Please consider contributing when you’ve found an article to be beneficial.

News

-

Linux Mint 22.2 Beta Available for Testing

Some interesting new additions and improvements are coming to Linux Mint. Check out the Linux Mint 22.2 Beta to give it a test run.

-

Debian 13.0 Officially Released

After two years of development, the latest iteration of Debian is now available with plenty of under-the-hood improvements.

-

Upcoming Changes for MXLinux

MXLinux 25 has plenty in store to please all types of users.

-

A New Linux AI Assistant in Town

Newelle, a Linux AI assistant, works with different LLMs and includes document parsing and profiles.

-

Linux Kernel 6.16 Released with Minor Fixes

The latest Linux kernel doesn't really include any big-ticket features, just a lot of lines of code.

-

EU Sovereign Tech Fund Gains Traction

OpenForum Europe recently released a report regarding a sovereign tech fund with backing from several significant entities.

-

FreeBSD Promises a Full Desktop Installer

FreeBSD has lacked an option to include a full desktop environment during installation.

-

Linux Hits an Important Milestone

If you pay attention to the news in the Linux-sphere, you've probably heard that the open source operating system recently crashed through a ceiling no one thought possible.

-

Plasma Bigscreen Returns

A developer discovered that the Plasma Bigscreen feature had been sitting untouched, so he decided to do something about it.

-

CachyOS Now Lets Users Choose Their Shell

Imagine getting the opportunity to select which shell you want during the installation of your favorite Linux distribution. That's now a thing.