Write a Novel with Open Source Tools

First Draft

ByIf you are looking for an open source tool to help you write your next novel, bibisco, ManusKript, and Plume Creator can help you get started.

Aspiring writers have no shortage of software that is supposed to help them along the road to a finished manuscript. Whether they are writing a short story or a multi-volume series, this software promises to organize them by providing software and revisable outlines, as well as a supposedly distraction-free full-screen mode and databases for characters, settings, objects, and drafts. On Windows and Mac, the leading software is Scrivener. However, since a Linux version of Scrivener has yet to reach general release, open source alternatives have sprung up like bibisco, Manuskript, and Plume Creator, each with its own approach to writing and outlining.

bibisco

Two years ago, I gave my opinion of bibisco in my Linux Magazine blog. Revisiting bibisco, I find my opinion unchanged: It’s a well-meaning piece of software that will appeal only to the minority who outline in fine-detail before they write. In fact, in my experience, those who outline as copiously as bibisco advocates typically put so much energy into preparation that their creative energies burn out before the first word of the opening chapter (Figure 1).

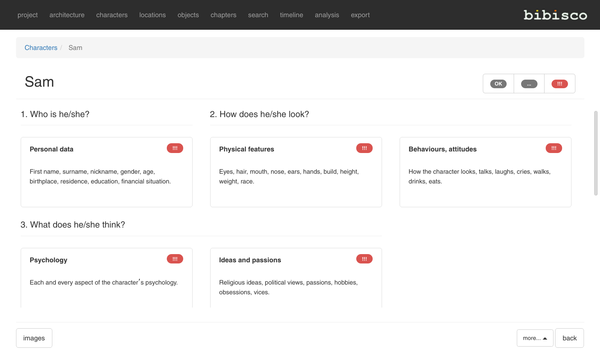

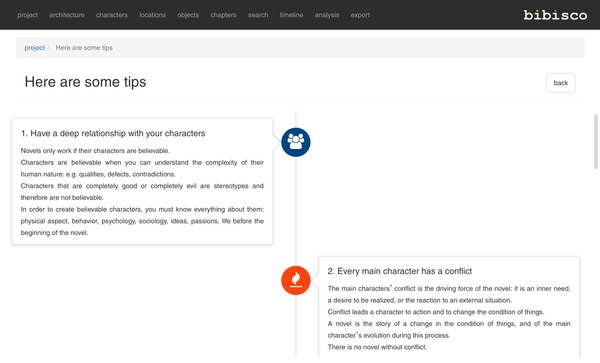

You can get an idea of Bibsco’s tendency from the way it handles characters. Bibisco’s first tip states that “in order to write believable characters, you must know everything about them” – and that apparently applies not only to main characters, but to minor characters as well (Figure 2). In pursuit of this knowledge, bibisco’s Characters tab offers nine different categories of questions to answer. Some, like the character’s physical description, are obviously useful, although I doubt that anyone needs to know every single detail; as my neighbor once pointed out to me, who remembers the color of Madame Bovary’s eyes? Similarly, I doubt that you need a character’s complete backstory ahead of time, let alone “every aspect of the character’s psychology.” In the best of circumstances, much of this detail is likely to be developed in a character’s interaction with others and the plot, and setting down this detail will be a waste of time for most people.

Much the same can be said for bibisco’s analytical features. A manuscript’s word length can be useful, although beginning writers tend to be obsessed with the statistic, with no regard for literary quality. But how often are you going to need to know all the scenes in which a character appears, or the different points of view used in each scene?

By contrast, other features, like the Locations are barely fleshed out at all -- proof, if any is needed, that bibisco’s makers view the novel as primarily about character. Nothing is wrong with this view, and it is, of course, a time-honored one. But when I think of the sense of wonder that Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings derives from fabulous settings like Rivendell, Lothlórien, and Minas Tirith, I realize just how limited bibisco’s view of writing can sometimes be. Moreover, other categories, like Objects and the Timeline, are available only in the paid version.

The worst thing about these limitations is that bibisco has by far the best interface, with functions laid out in a menu across the top of the screen and options arranged in buttons or sidebars across the window. Attractive as this interface may be, its usefulness is limited thanks to bibisco’s insistence that users do things its way.

Manuskript

Manuskript does not attempt bibisco’s detail. Admittedly, when you start a new project, it asks for a genre, although exactly what the structural difference between a novel and, say, a trilogy is not clear. It appears to be a matter of how many levels are in a hierarchy: A novel is divided into Acts, Chapters, and Scenes, and a trilogy adds Books at the top of the hierarchy. At the start, you are asked how many of each level you want, although how you should know when you have not already started outlining is a bit of a puzzle. Nor are making choices easy, because the opening windows are only partially visible until you drag on their edges (Figure 3).

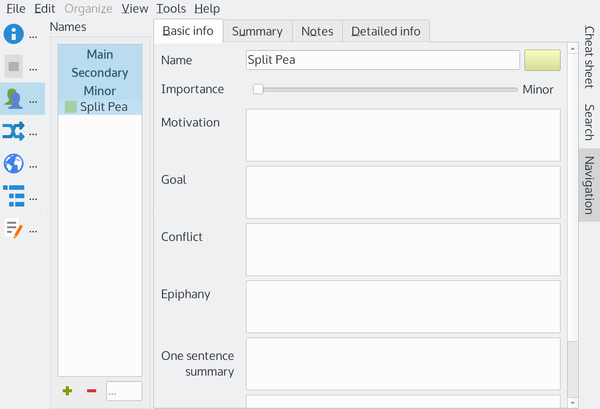

However, once you actually get down to planning, Manuskript is much less dogmatic. The interface favors one sentence summaries that can be expanded into paragraph-long summaries for every aspect of a work, but usually it offers only a brief title and an entry field with no required fields. For example, the Basic Info tab for a character contains fields titled Motivation, Goal, Conflict, and Epiphany, leaving you the choice of which to complete. If, like me, you consider the first three fields synonymous and do not see characters in terms of epiphanies, you can leave some of the fields blank. Other parts of the structure have a similar freedom, leaving you to decide, for example, what goes on the Notes tab as opposed to the Detailed info tab. Probably you will want consistency, but, on the whole Manuskript has a freedom that bibisco lacks.

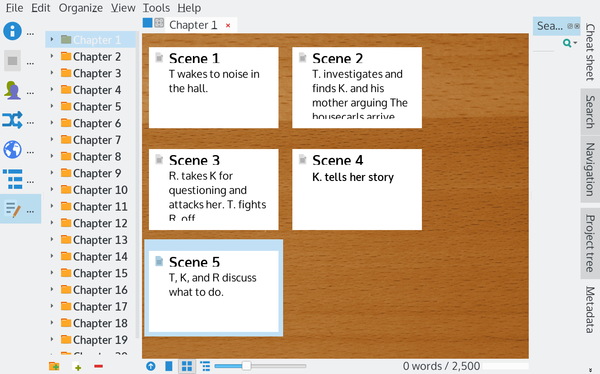

One handy feature of Manuskript is its Scrivener-like storyboard, with a menu of chapters on the left and fields for each scene on the right. While scenes cannot be added from the storyboard, scenes can be deleted and shuffled, and detailed views are only a click away, all of which makes Manuskript an ideal tool for initial planning (Figure 4).

Plume Creator

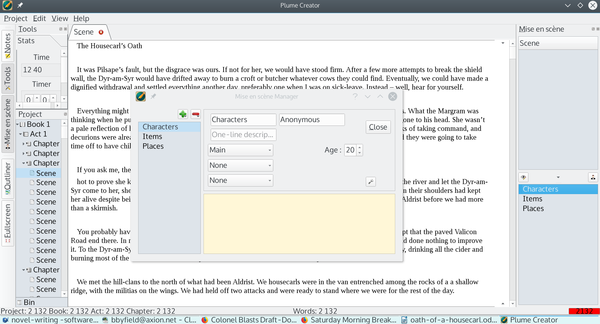

Like Manuskript, Plume Creator offers a clear and open-ended approach to outlining. Although the initial distinction between a novel and a long novel is unclear, once you are at the main window, the layout is clear enough, with a menu in the left margin and an editable table of contents to the right of that. To the far right are secondary content, such as lists of Characters, Items, and Places. If Tools is selected, you can toggle a timer, a feature that many beginners use in writing sprints. At the bottom right, the current word count is highlighted in red; this can also display the target word count. The Outliner tab allows items to be listed by draft number, providing a basic tool for version control.

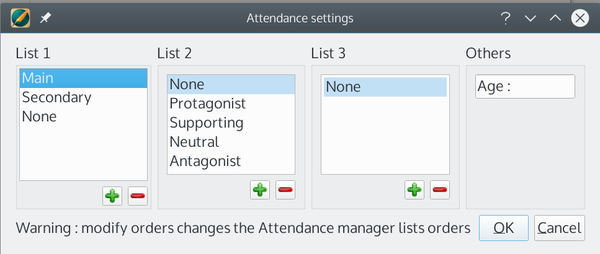

Plume Creator’s open-end approach can be seen in its treatment of Characters, Items, and Place (Figure 5). Each item can have a name and an alias, as well as three characteristics that are chosen from a drop-down list. For characters, the first two drop-downs are the importance and role of the character, while the third is left blank for customizing. To the right, the character’s age can be set. Anything else must be added to the Notes field below. This arrangement is about as far from bibisco’s details, marred only by the fact that just three drop-down lists are allowed, and that the defaults for characters also appear for items and places (Figure 6).

Still, once customized, the editing windows are clear enough for the high-level planning typical of most writer’s initial outlines. If Plume Creator seems unfleshed-out compared to bibisco or Manuskript, its layout seems more realistic and flexible.

A Solution in Search of a Problem

An annoying feature of all three of these applications is that their input is strictly manual. All three have a full-screen mode with a minimum of features so that you can write without considering format, but using any of these applications at all means manual formatting, and, more often than not, a second pass through the manuscript to finalize formatting. I would far rather use my fiction template in LibreOffice that sets which style follows which. Using the template also allows me to forget about format, but does not require a second pass through the manuscript. Moreover, if I do want to make format changes afterwards, I can do so in a fraction of the time required in these novel-writing applications.

But my greatest reservation is the assumption that detailed outlines are an absolute requirement before you write. Even a well-known writer like Neil Gaiman says in his master class that the first draft is like driving in the fog, while the second draft is about creating the illusion that you knew what you were doing in the first. In other words, Gaiman does not begin knowing all the details of his story or his characters and instead discovers much of the story during the writing process. Nor, in my experience, is he alone in his work flow. If anything, he is part of an overwhelming majority.

It seems to me that the problem with all three of these applications is that using them in the way that they are intended can easily be a distraction from the actual writing. They create an illusion of progress, yet, in the end, I suspect that they result in copious notes and no manuscript or wish to produce one. All three could learn from Krita, which only soared to excellence when it started to listen to those who would actually use it.

(Bruce Byfield is two-thirds through the writing of his first novel.)

next page » 1 2

Subscribe to our Linux Newsletters

Find Linux and Open Source Jobs

Subscribe to our ADMIN Newsletters

Support Our Work

Linux Magazine content is made possible with support from readers like you. Please consider contributing when you’ve found an article to be beneficial.

News

-

LibreOffice 26.2 Now Available

With new features, improvements, and bug fixes, LibreOffice 26.2 delivers a modern, polished office suite without compromise.

-

Linux Kernel Project Releases Project Continuity Document

What happens to Linux when there's no Linus? It's a question many of us have asked over the years, and it seems it's also on the minds of the Linux kernel project.

-

Mecha Systems Introduces Linux Handheld

Mecha Systems has revealed its Mecha Comet, a new handheld computer powered by – you guessed it – Linux.

-

MX Linux 25.1 Features Dual Init System ISO

The latest release of MX Linux caters to lovers of two different init systems and even offers instructions on how to transition.

-

Photoshop on Linux?

A developer has patched Wine so that it'll run specific versions of Photoshop that depend on Adobe Creative Cloud.

-

Linux Mint 22.3 Now Available with New Tools

Linux Mint 22.3 has been released with a pair of new tools for system admins and some pretty cool new features.

-

New Linux Malware Targets Cloud-Based Linux Installations

VoidLink, a new Linux malware, should be of real concern because of its stealth and customization.

-

Say Goodbye to Middle-Mouse Paste

Both Gnome and Firefox have proposed getting rid of a long-time favorite Linux feature.

-

Manjaro 26.0 Primary Desktop Environments Default to Wayland

If you want to stick with X.Org, you'll be limited to the desktop environments you can choose.

-

Mozilla Plans to AI-ify Firefox

With a new CEO in control, Mozilla is doubling down on a strategy of trust, all the while leaning into AI.